4 Kings in a Row Died From Smoking

Is addiction too hardwired to overcome? Are men just bad at health?

Finally binged Netflix’s The Crown, a million years late! The first couple episodes deal with the death of Queen Elizabeth’s father, King George VI, who was a heavy smoker and died from related complications. My own father, also a smoker, passed away in January after a stage IV lung cancer diagnosis thirteen months earlier. Consequently, the first couple episodes of The Crown were a little tender for me. Almost six months passed before I could revisit the show.

Once back into the series, it was impossible not to Google what was truth and what was fiction. And I made a (new to me) discovery: four British kings in a row died from smoking-related complications. FOUR IN A ROW. That’s wild!

It starts with Queen Elizabeth’s dad, King George VI:

George VI was a heavy smoker and consequently developed arteriosclerosis and Buerger’s disease: blood vessel disorders that result in thickened arteries with abnormal clotting. In 1951, his entire left lung was removed after the discovery of a “structural abnormality”: in reality, it was lung cancer. Amazingly, royal doctors withheld the cancer diagnosis from the King himself, the general public, and the rest of the medical community. George VI recovered from the surgery, however he continued to cough up blood, which suggests the cancer likely spread to his right lung.

He passed away unexpectedly in his sleep in 1952 at the age of 56. At the time, it was assumed his cause of death was a “coronary thrombosis”, or blood clot in the heart. In 2021, researchers examined the cardiovascular and oncologic evidence available and proposed an alternate hypothesis: metastasis of his lung cancer could have caused a pulmonary embolism or intra-thoracic hemorrhage.

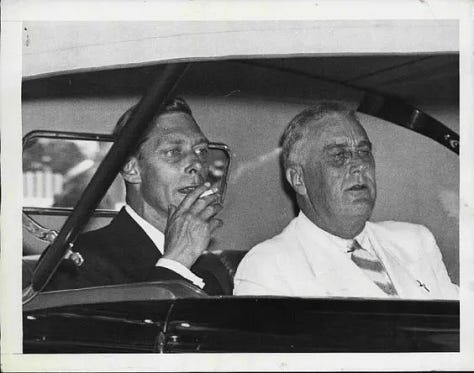

Next up was Edward VIII, George’s older brother, infamously known for abdicating the British throne after just eleven months to marry American divorcee Wallis Simpson:

Edward was a lifelong, heavy smoker: pipes, cigarettes, and cigars. He did it all and seemed to take no lessons from his brother’s untimely death. His health began to fail in the 1960s, and in late 1971, he was diagnosed with throat cancer. On May 18th, 1972, Queen Elizabeth visited her uncle at Villa Windsor in France, detouring from a state visit. Edward was reportedly “too ill to the leave the first floor sitting room”, and their visit was short. He succumbed to the cancer just ten days later. He was 77.

(Edward VIII’s questionable judgment was further illuminated when I discovered he was quite possibly a Nazi sympathizer. Wow.)

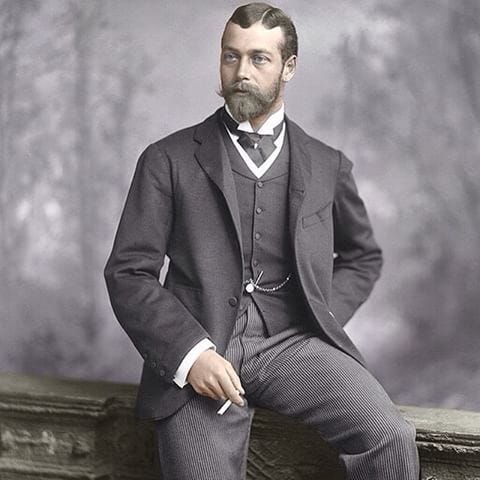

What about their dad? He was George V (another George, confusingly). This would have been Queen Elizabeth’s grandfather:

I obviously don’t condone smoking, but…he had, as the kids these days say, some “rizz”.

That being said, George had suffered chronic bronchitis, made worse by smoking, since World War I. He likely developed something like COPD and was using supplemental oxygen in 1935. By the beginning of 1936, George was on his deathbed. In 1986, it was discovered that his personal physician made the decision to inject him with morphine to hasten his death for announcement in the morning papers. He was 70.

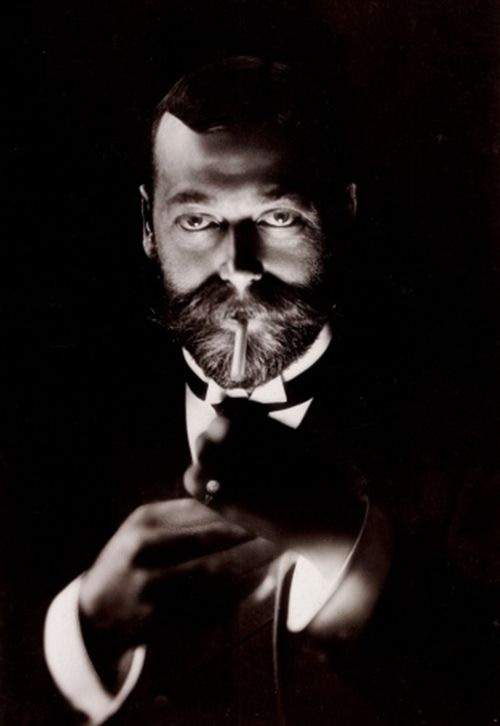

So that’s three. Did they not realize smoking was the common denominator? Did they not care? Just for fun, I decided to go back one more generation. This was Edward VII (another Edward, confusingly), and Queen Victoria’s son:

Edward VII loved cigarettes and cigars — he famously quit his London gentleman’s club in 1866 over its no-smoking policy and took twenty percent of the membership with him to a new one.

Queen Victoria (smartly!) did not approve of the habit, so it was banned in her presence and effectively, in upperclass public society. When Edward VII was crowned king in 1901, he famously announced after dinner, “Gentlemen, you may smoke”. Edward’s image graced the cover of Prince Albert tobacco cans (Albert was his given name), and he is credited with the invention of a tail-less smoking jacket to wear to dinners at his Sandringham estate. This became known in America as the tuxedo.

The habit caught up with him, and towards the end of his life, he was suffering from increasing bouts of bronchitis. By 1910, he was unable to shake a severe case of bronchitis that followed him home from a trip to France. This, combined with several heart attacks (likely the culmination of smoking-related cardiovascular disease, as seen in George VI) ended his life. He was 68.

Welp! Four in a row. Guess who broke the streak on either end?

Queens Victoria and Elizabeth1. So this begs the question: is addiction so hardwired that it’s nearly impossible to overcome, or are men just terrible at taking care of their health?

Addiction and the general way our brains and personalities are wired is a certainly an important factor. Turns out there’s lots of discussion on the health thing: in short, yes, men are quite bad at it! Men use less preventative health care services and don’t seek immediate treatment for many health problems. (This tracks: we basically had to bully my dad into getting his tooth abscess seen at the dentist not once, but twice!) A 2011 study showed that if a man does not have a vigilant spouse, he is not likely to have an annual wellness exam or even a regular doctor! Why is this? Many studies reached a conclusion that is likely obvious to most of us: masculine norms. Yes, toxic masculinity strikes again.

Masculinity has traditionally embodied certain ideals: independence, resilience, stoicism, self-reliance, and pain tolerance. Outwardly demonstrating masculinity is also an important part of masculinity itself. One study showed men are more likely than women to engage in riskier behavior (I mean, we’ve boys-will-be-boys’d smoking, alcohol use, physical stunts, and fighting), and men hold riskier beliefs. All of these things mean men are more likely to engage in unhealthy behaviors, and they’re socialized to avoid seeking health care to deal with the repercussions of those behaviors. (Guess who does deal with the repercussions? Women! But that’s another essay for another day.)

The masculine norms pop up everywhere. Many men tend to continue past family norms (e.g. “when I was a kid, my dad put superglue on my cut and I was fine!”). They’re more likely than women to use concerns about money and missing work as a reason to avoid treatment and a hefty medical bill — a clear (and somewhat detrimental) legacy of the twentieth century emphasis on the “male breadwinner” and the pressure men (and society) place on themselves to support a family.

Masculine norms can even affect how men learn about health. Women are socialized to connect with, and confide in, other women, friends, family, etc. regarding health issues. (Likely stemming from the lack of research into women’s health — another essay for another day!) Women are more likely to turn to magazines, books, TV, and social media to seek knowledge and information. Men do not do this! At least not to the same degree women do. Socioeconomic level, race, and occupation also affect how men interact with health care.

Gender differences regarding mental health are possibly the most crucial piece of this puzzle. Men make up the majority of suicide and substance abuse disorder diagnoses, however their anxiety and depression rates are half that of women. That doesn’t track! What’s going on there?

Some research suggests men display depression differently than women: instead of exhibiting the classic depressive symptoms, they might “act out” with substance abuse, risk taking, poor impulse control, and increased anger and irritability. This means their depression goes under or mis-diagnosed. The discrepancy between men’s statistically low rate of depression and their higher rate of suicide certainly supports this.

Men are also very bad at perceiving and identifying symptoms and diseases within their bodies. I don’t have a citation for this one, but anyone who’s had a Baby Boomer male in their lives knows this is true. They are not particularly self-aware! Masculine norms can certainly play a role in this tendency to ignore and blunt the reporting of physical and mental problems.

Finally, men are just less likely to seek mental health treatment than women. They turn to things like alcohol and smoking to cope, and their higher rates of substance abuse disorders underline this. Masculine norms and societal expectations are certainly to blame here, and to a devastating effect: men have a lower life expectancy than women. On average, they live five to seven years less.

There’s a final conclusion to draw from all this: sometimes people don’t learn. Can’t learn. Won’t learn? And that is the brutal teamwork of genetics, of social and gender norms, and the general pressures of being a human being. The good die young, and this is very often men. And these men are very much loved. They’re husbands, fathers, brothers, and friends. In their wake, they leave grief. Open thrones. Grandchildren they’ll never meet. Spouses who must forge a new life in their absence. And a daughter who’d very much like to spend one more morning drinking coffee and doing the crossword with her dad.

Honorable mention to Princess Margaret, Queen Elizabeth’s sister: she (sadly) seemed to inherit her father’s inclination for smoking. Part of her lung was removed in 1985, and she suffered repeated bouts of pneumonia and several strokes, the last of which ended her life at age 71. Her mother and sister, non-smokers, would go on to live almost thirty more years.